UA historian helping bring slave ads to light

There is a universal desire among people to be free.

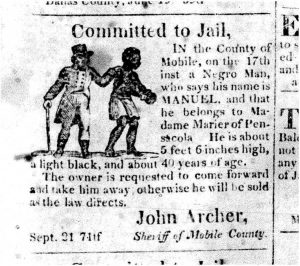

This overarching message consistently rings loud and clear through thousands of runaway slave advertisements published in newspapers in antebellum and colonial America. Wherever enslaved people lived, enslaved people ran away, and their enslavers advertised in an attempt to recapture them.

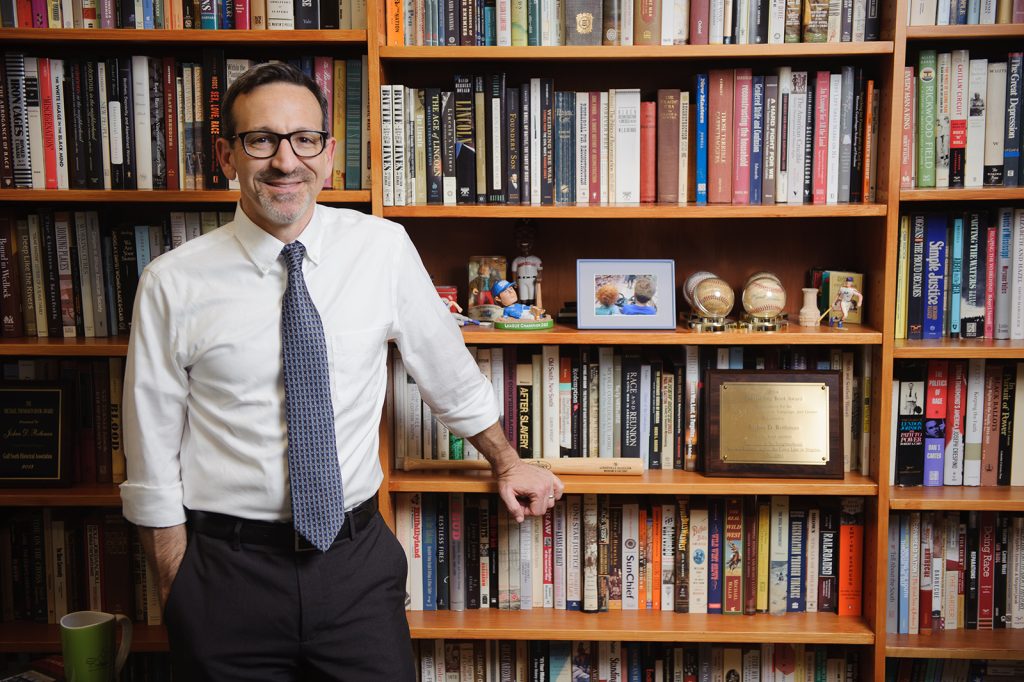

“You still sometimes hear among Americans the suggestion that enslaved people should have resisted more,” said Dr. Joshua Rothman, a historian at The University of Alabama.

The South’s “lost cause” ideology sometimes envisioned enslaved people as happy, but these were stories white people told themselves to avoid dealing with the ramifications of chattel slavery of Africans and their descendants, he said.

“What these ads tell you is that the notions of complacent or even happy enslaved people are false,” Rothman said. “What the stories embedded in these advertisements indicate is that the resistance of enslaved people was a constant.”

Rothman is part of an effort to complete a comprehensive database containing every runaway slave advertisement in American newspapers prior to the Civil War. The digital humanities project, called Freedom on the Move, began about five years ago at Cornell University and is a partnership with UA and the universities of Kentucky and New Orleans.

Although the idea to create the database existed for some time, it started developing after researchers at several universities discovered iterations of it were underway at multiple institutions. The professors combined efforts into a single project, Rothman said.

Thus far, the cross-university team of historians has collected about 50,000 ads for the database but believe as many as 200,000 ads will be available when the project is complete.

“What we’re trying to do is both very straightforward and very daunting at the same time, which is try to pull together every single runaway advertisement that appeared in an American newspaper,” Rothman said. “That’s every newspaper in the South and even newspapers in the North, if you go back to a time when slavery existed in Northern colonies and states.”

The ads collected aren’t concentrated in any particular state. Of course, the antebellum South produced more runaway slave ads than Northern states because slavery was concentrated there, but no region of the South appears uniquely prolific in its ad production.

“If I go back to the 18th century I can pull up runaway ads in Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania,” Rothman said. “Any place where people were enslaved, there were going to be people who decided they did not want to be enslaved anymore and were willing to take the chance of flight.”

He said the ads are what most people would expect them to be, reducing people to lost property. Slaves were worth money. Sometimes a lot of money. So, when they ran, their “masters” would place ads containing detailed descriptions in hopes of getting them back.

A reward was offered nearly every time, but the stipulations of the award varied based on the conditions of the returned runaways. Sometimes the ads would state a person would receive a certain amount if they brought a runaway back alive, another amount if they put the escaped slave in jail and another amount if they brought the person back dead.

Typically, enslavers wanted the person back alive, but sometimes ads would state things as, “I don’t care what you do, if you bring them back dead, that’s good enough,” indicating something may have occurred during the escape that caused the slaveowner to seek vengeance, Rothman said.

“You can think of them as wanted posters, except the people in them were wanted for the crime of wanting to be free,” he said.

Surprising details researchers discovered in the ads were the lengths people would go to in order to escape, and the detailed information slaveowners knew about their slaves.

“Slaveholders sometimes seemed to know incredible details about enslaved people, like where they came from and where they think they’re going to go,” he said. “They sometimes will describe runaways in column-length ads, almost like a miniature biography.”

Those long ads would contain details about the runaway such as whether they might pretend to be white, wear a disguise by dressing in men’s or women’s clothing, or likely flee north or somewhere else such as Texas, especially when Texas was still a part of Mexico. The ads also listed the person’s age, build and marriage status. The ads would also contain information about if the runaways would try to hide out in New Orleans or other places in the South where they might have family.

“These people wanted to be free, but getting to a free state was not always their priority,” he said. “A lot of the times it was just to get to a place where they could be safe or reconnect with their wife and kids.”

When the database launches, it will be free and open to the public. Rothman said the Freedom on the Move project will be a useful resource for academic scholars, and middle, high school and college students.

“We’ve already done some testing of it in classrooms in a few different places,” he said. “You turn students loose and allow them to pick ads in whatever state they want to look at them.

“It’s an amazing teaching tool because these documents are short, accessible, easy to understand, and they let students identify with individual people that other documents about slavery don’t allow you to do.”

Dr. Rothman is professor and chair of the UA history department. Freedom on the Move is supported by about $1 million, including grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Historical Publications & Records Commission.