Researchers Explore Biomass Potential to Replace Petrochemicals

By Richard LeComte

Photos by Jeff Hanson

For years, manufacturers of some pharmaceuticals or everyday items made of plastic have relied on non-renewable petrochemicals that gush from the bowels of the Earth — black gold, Texas tea – as a key ingredient.

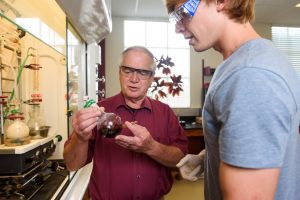

Now Dr. Anthony J. Arduengo III, a University of Alabama chemistry professor, and an international group of scientists are working to replace petrochemicals with a much more chemically complex component that grows, rather than springs, from the ground – wood.

“Wood, a renewable resource that’s easily accessible, offers the opportunity to directly harvest a wide range of building blocks with diverse chemistries and structures that can then be used to build materials for the modern world,” Arduengo says. “Just imagine a modern ‘oil boom’ or ‘gusher age’ that is not based on oil and petrochemicals, but rather the renewable resource of wood.”

Arduengo is a co-founder of an international consortium called STANCE. The consortium, whose website may be found at https://xylochemistry.com/portal/, includes faculty members and students at UA and the Institute for Organic Chemistry at the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany, as well as professors at institutions in Japan, Canada and the United States.

The purpose of the consortium is to spread the word about research involving replacing petrochemicals with renewable biomasses – wood and possibly seeds and leaves – in the making of a host of different materials.

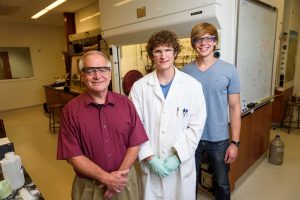

“We’ve been extremely active,” Arduengo says. “A big part of this new technology is training scientists and students to take advantage of this technology when it’s in place. These days, the education we receive is based on petro-chemistry, so if we’re going to move into a new technological area and you’re going to rewrite this infrastructure, then you’ll need scientists who are trained a little bit differently.”

And what does this new technology entail? Arduengo’s near-missionary zeal for finding new processes is rooted in his love of chemistry and the environment. For years, manufacturers have found it much easier to use different forms of petrochemicals in their processes simply because they’ve always done it that way.

“Petroleum was cheap and easily available, and in the old days it would pop out of the ground in places where you didn’t want it,” Arduengo says. “It didn’t have much value at the time. Of course, there were tremendous deposits to it. Once you develop the technology for getting it out of the ground, it provides a convenient starting material. The one strength you can point to is that they’re biomaterials in their simplest form.”

But with advances in chemistry, materials with more complex organic structures – wood, for example – can now take the place of petrochemicals.

“Petroleum has tremendous disadvantage,” Arduengo says. “Most of the functionality that was originally there has been cooked out of it after eons of high temperatures and pressure. With wood, we know enough about chemical processes now that we can build small molecular-modules or ‘building blocks’ out of biomasses like wood, seeds or the shells around seeds, leaves or bark from trees.”

Using trees and other renewable biomasses may have a much greater ecological impact than simply replacing oil. Arduengo points out that managed forests producing wood for the chemical industry can help to reduce carbon in the atmosphere.

“Those young forests absorb a lot more CO2 from the air and release more oxygen than an old forest does,” he says. “An old tree that won’t grow much anymore won’t need as much carbon, but a young tree will take a lot more CO2 from the atmosphere. So these young forests are a tremendous boom to the cycle of CO2 in the atmosphere.”

STANCE, the consortium that seeks to spread research about xylochemistry to manufacturers and other scholars, has made several key results public, including a recent cover article in the German publication Angewandte Chemie.

But some of the explorations remain private. STANCE has a two-level website: one for the public and one for the members to exchange information that might be proprietary. Arduengo sees several specific applications for Xylochemistry, but they await takers from manufactures.

“I can point to a couple of things generally,” Arduengo says. “The specifics are there, but we’re waiting on industrial partners to grab on to the pieces of technology. The general areas are plastics – we have some routes to some plastics and plastic replacement materials that we can make directly from wood.

“We have some new dye stuffs that provide pigments for paints. We’re also working on some UV protectants – products that would absorb harmful UV rays and either protect skin or protect materials in the case of plastics. Another area we’ve been active in is making pharmaceutical pieces – units that can be built into a pharmaceutical molecule.”

The research has excited his colleagues, particularly Dr. Till Opatz, the consortium’s European coordinator and professor at Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz. Opatz has appeared on German television to discuss the potential of xylochemistry.

“Dr. Arduengo’s work involves, among others, the development of new chemical processes and of new catalysts for running them under eco-friendly conditions,” Opatz says. “Due to his strong links to the industrial sector – he has been a research leader and supervisor at DuPont earlier in his career – Dr. Arduengo has a profound knowledge of industrial chemistry and the requirements associated with bringing products on the market. Plus, it is a sheer pleasure to discuss and to work with him.”

In addition to the work in organic chemistry, STANCE operates an active scholar-and-student exchange. Two German students recently worked with Arduengo at his lab in Shelby Hall, and Arduengo has sent UA students to work in Germany. Opatz and Arduengo also trade continents to further their research. Arduengo sees a strong educational component to all his research.

“I often make the argument to my introductory chemistry classes that one reason why humans are so successful as a species is that we’re inherently chemists,” Arduengo says. “If you go back in the history of humankind and think of those initial discoveries that were important to us, building a shelter – if you think about it, building a shelter requires material science. Is it better to use a material like stone or straw when you’re building a house or some kind of wood structure?

“If you want to keep warm, you need fire. Well, fire is an oxidation process. You need combustibles and oxygen. That process provides both heat and light. Those are the beginnings of chemistry.”

And, along with the educational and ecological prospects for xylochemistry and the STANCE consortium, Arduengo sees a tremendous opportunity to help the economy of Alabama through the switch of some processes from petrochemicals to wood.

“Alabama is a natural place for this technology to develop,” he says. “It’s already a major player in forestry and wood raw materials. If you want to look at something that would be a tremendous boom to Alabama, switching over from petroleum to wood-based materials, we could develop a chemical industry that is sustainable and environmentally friendly with the resources we have in Alabama. It’s a tremendous opportunity.”

Dr. Arduengo is the Saxon Professor of Chemistry within UA’s College of Arts and Sciences.