TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — A University of Alabama faculty member is mapping Florida Bay in Everglades National Park.

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — A University of Alabama faculty member is mapping Florida Bay in Everglades National Park.

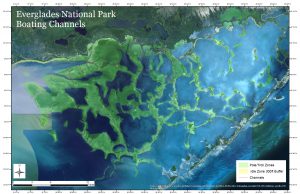

Dr. Michael Steinberg, associate professor in New College and geography, and Brad Bates, a graduate assistant to Steinberg, are developing an accurate map of the channels and flats to help ensure the conservation of the bay.

The map is crucial to slowing the habitat damage caused by boats and other external, man-made forces, Steinberg said. The Bonefish and Tarpon Trust commissioned and funded the map to help the National Park Service. According to Steinberg, the trust contacted him because of his cartography lab at UA as well as past research with the trust.

“The environmental issues caused by humans are hard to quantify, but most of them stem from issues to the north (in Miami),” Steinberg said.

Steinberg also said that the park hopes to use the map to institute “pole and troll” zones in Florida Bay to avoid excessive boat traffic.

“If you have a lot of boat traffic through the bay, the wakes can destroy nesting sites for birds and sea turtles,” he said. “It’s a big enough problem that the Park Service has said, ‘We’ve got to do something about this.’

“They want to limit the effect that boat traffic has on areas where animals will be nesting,” Steinberg said. “There are large numbers of manatees in the bay, and they love these shallow water areas, so they face a great potential for conflict with these boats. Those powerful outboards on the boats can do a lot of damage to the manatees.”

Steinberg said turtle grass is a major part of the habitats that are being destroyed. Turtle grass can take seven years to grow back. In that time, the bottom of the bay can undergo severe changes in the absence of the grass to hold the sand in place.

“Most of the seagrass issues are attributed to human activities, rather than natural activities,” Steinberg said. “The absence of seagrass causes more wave activity that can destroy habitats, and that’s when you start getting into trouble.”

Bates said that prop scars from boat motors also play a part in the destruction of the grass beds.

“You’re not only making a fragmented habitat by doing that, you’re also stirring up sediment that resettles and can reduce the amount of sunlight that the seagrass beds can actually get,” he said.

Steinberg compared it to erosion and desertification on land, with the water currents acting like the wind in the desert.

“Once the current and the tide interact with these barren areas, it’s really hard for seagrass to grow back, and that leads to more destruction and erosion in those areas,” he said.

Steinberg also cited the connection between the environment and the economy of the Florida Keys as a major factor in the importance of the map and preserving the ecosystem of Florida Bay. Ground-truthing is the process of going to the site and “see what you’re seeing,” as Steinberg put it. He said they do ground-truthing as a means of verifying the satellite images of the bay.

“Satellite images can be very accurate, but even with really good images, you still have to ground-truth certain things,” he said. According to Steinberg and Bates, satellite images can be compromised by things such as cloud cover or a poor picture in one section.

By going to the site and performing the ground-truthing, Steinberg said they learned more about the importance of these areas to the animals and the humans that call Florida Bay home.

Contact

McKinley Cole Lanier or Richard LeComte, media relations, rllecomte@ur.ua.edu, 205/348-3782

Source

Dr. Michael Steinberg, 205/348-0349, mksteinberg@as.ua.edu