By Chris Bryant

Photos by Zach Riggins

Some people enjoy tracking spring’s first robin. Others … well … they get their buzz from focusing on smaller winged creatures.

“People make fun of me because I go out and do bee watching,” says Dr. Jeff Lozier, a University of Alabama biologist who specializes in bumble bees. “I go out, and I write down when I see the first queens of the year. I’ve found six species of bumble bees in town.”

His interest in, and his knowledge of, the plump, black and yellow insects seemingly is endless. And the extent to which he’ll go to collect one for his research apparently knows few limits.

Odds seem good that, while you’re reading this, Lozier and a couple of his science buddies are out there, nets in hand, battling the elements. Sometimes they’re climbing mountains, literally. Other times, they’re unsuccessfully dodging curious glances from passers-by. A few bold souls stop and ask. Most leave ’em be.

“If someone is doing something crazy enough like hanging off the edge of a cliff with a net, trying to catch a bee, they probably figure, ‘Hey, this guy is either insane or he knows what he’s doing, so we’re just going to leave him alone.’”

Crazy like a fox, perhaps. The National Science Foundation recently awarded Lozier and two collaborators at the University of Wyoming and Utah State a $1 million grant to better understand how two specific bumble bee species cope with environmental variability.

As the principal investigator of the project, Lozier, you might say, is the king bee. His piece of the grant? Almost $600,000. Who’s making fun now?

Responding to bumble bee questions seems as natural for Lozier as a bee tracking pollen. Just try him.

Q: How many species of bees are there?

A: There are thousands of described species of bees. There are approximately 250 species of bumble bees, 45-50 species in the U.S.

Q: Can bumble bees fly in the rain?

A: Yes.

Q: Can bumble bees sting?

A: Yes. The females have stingers. The males don’t … like most bees.

Q: You ever been stung?

A: Three or four times, and I’ve collected thousands of bees. They don’t like being stuck in tubes and being put in nets. But, in terms of just walking around outside, I don’t know of anyone who has been stung by a bumble bee. It took you a while to get that one. That’s the first question most people ask.

Q: Bumble bees don’t appear very svelte. How far can they fly?

A: There is documentation of individual queens moving over 100 miles in a single year.

Q: What are bumble bees good at?

A: If you buy a tomato, chances are, it has been pollinated by a bumble bee. They are quite good at it.

Q: What’s up with the bee decline? If they die off, are we all going to die?

A: We’re not all going to die. There are lots of things that are wind pollinated. There are lots of things that pollinate. It’s not so much that the world is going to end if we have these pollinator declines. What it means is, it becomes harder and harder to naturally achieve these services that pollinators have provided us for a very long time.

But, the decline is a concern, Lozier says, and it’s something scientists are attempting to sort out.

“It’s a problem,” Lozier says. “Is it an insurmountable problem? No. I would be disappointed if all the bees die, but I don’t think it’s going to happen anytime soon.

“Study after study demonstrates that having a diversity of pollinators in an environment improves yield, and it improves quality. Having honeybees and bumble bees together pollinating a crop improves the yield and quality of the crop versus having an equal number of honeybees, alone.”

If one species declines, another, Lozier says, frequently picks up the slack.

“Diversity is important, and you hate to lose anything. The world changes. I’m sort of practical about it. I try not to get too grandiose about the consequences of these things.”

While working as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Illinois, Lozier was part of a team that conducted a broad survey of bumble bees across much of the United States in an attempt to gauge their prominence.

“Certain species are doing just fine,” Lozier says. “They are everywhere. Other species are either dramatically less abundant where they are found or their ranges are shifting or shrinking relative to the historical ranges.”

Cultured honeybees, housed by beekeepers, saw a sharp decline in recent years and a sharp spike in notoriety. “Colony collapse disorder,” as the problem was named, received widespread attention in media outlets worldwide.

Bees, including honeybees, gradually have declined over the last 50 years, Lozier says.

In May, new data indicated almost 25 percent of U.S. honeybee colonies died this year. Many suggest the rate is too high for the species to survive. In combination with the historic numbers, it’s evident that the reasons behind the declines are complex, Lozier says.

“There’s been a general malaise, a general decline in wild pollinator populations, including bumble bees.”

In some cases, a specific fungus, Nosema, may be partly to blame, Lozier says. Pesticides are also likely factors in the decline, he says. The Environmental Protection Agency recently issued a moratorium on the use of Neonicotinoids – one class of pesticide some believe is heavily responsible for the declines.

In spring of 2015, the White House issued the “Pollinator Research Action Plan,” a 57-page report outlining a course of action. According to the report, further research is needed “to fully understand the factors that drive population trends.”

Climate change, which can alter bees’ habitats, is another factor frequently cited in bee declines.

Efforts by Lozier and his collaborators to better understand how species have evolutionarily coped with variations in their environment have implications for predicting likely responses to climate change, Lozier says. The scientist cautions, however, that specific predictions are likely years down the road and would, in addition to the bee research, hinge on the development of an accurate climate change model … a seemingly elusive goal at present.

But one has to start somewhere. And where Lozier and his colleagues are starting is in California. Over the course of the summer, spots in Oregon and Washington will be added.

Equipped with nets, a cooler of dry ice for preserving the specimens, scales for weighing the captured bees and vials for storage and mailing the bees back to campus labs, the trio headed for a couple of weeks of collecting in early May.

Collection targets include 400 to 500 bees of each of the two specified species. The scientists planned to collect bees from both low and high altitude sites at five to six latitude points.

“You expect there to be unique genetic adaptations to a lifestyle of living on mountains versus living down at low elevations,” Lozier says.

A primary goal of the project, he said, is to identity some of the evolutionary adaptations that bees have across the geographic range in the diversity of environments in which they live.

Variation in things like oxygen levels, air density, ultraviolet radiation, temperature and precipitation create differing pressures on bees in the different environments. Some factors change with altitude but remain stable with latitudinal changes.

“It allows you to decouple, by combining both latitude and altitude, some of these different pressures,” he said. “We’re quite interested, for example, in some of the molecular mechanisms associated with flight and whether or not populations that are typically collected from low altitude, low latitudes sites are differentially adapted for flight at particular elevations from populations that are sampled, for example, at 10,000 feet.

“Is living in a cold environment on top of a mountain different than living in a cold environment in Washington state, and how is that going to impact whether or not populations are going to be able to adapt to their shifting environments in the future?” Lozier asks. “And how capable are populations of migrating or dispersing? Are we going to see increasing fragmentation … inbreeding?”

Those are the types of questions they hope to begin answering.

After the bees are collected, DNA is extracted from the bees’ muscle tissue, and large portions of their genomes are sequenced.

“We correlate genetic data with environmental data to try and identify associations,” Lozier says. “The goal is to identify regions of the genome that are involved with adaptation.”

Scientists weigh the bees in the field, both before and after the pollen the bees are carrying is scraped away and nectar squeezed out. This way, the scientists know exactly how much weight each bee was carrying.

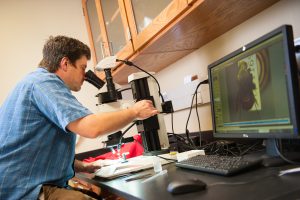

Wings are later removed from every specimen and they, along with the bodies, are individually imaged using microscopes.

Lozier refers to the overall work as molecular ecology – an effort to use genetics and other molecular tools to answer questions about ecology and evolution.

“It’s an exciting time to be a biologist,” Lozier says.

“If anything has DNA, you can kind of do what I do with it. People use similar methods that I do with humans and every other organism on the planet.

“The bees … I just quite like them.”

Dr. Lozier is an assistant professor of biological sciences within UA’s College of Arts and Sciences.