Dr. Robert Mellown’s research into the architecture of The University of Alabama has uncovered 180 years of campus designers’ and builders’ plans and dreams. These plans, and the buildings they inspired, continue influencing the 21st century campus.

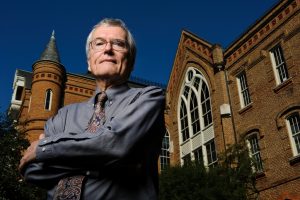

Mellown, a retired UA professor with expertise in Southern architecture, is preparing a book, “The University of Alabama: A Guide to the Campus and its Architecture,” a larger, expanded follow-up to his 1988 guide.

The new book is not just a guide but also a study of the complex historical and architectural development of the state’s oldest institution of higher learning.

Mellown began studying the architectural history of the campus while working with Suzanne Rau Wolfe on her “The University of Alabama: A Pictorial History” published by The University of Alabama Press in 1983.

“The University was a planned institution from the beginning,” says Mellown, who teaches 19th century art and architecture. “Unlike many schools and colleges that have simply evolved over time, the University is based on a series of master plans — none of which were followed exactly — but all of which have influenced later developments. In the book, I examine the rationale behind the plans and examine how they have shaped the campus as we experience it today.”

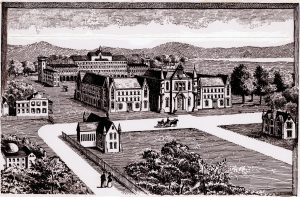

William Nichols, an English-born architect designed the earliest plan for the campus in 1828. It was partially based on Thomas Jefferson’s plans for the University of Virginia campus in Charlottesville.

Like Jefferson, Nichols envisioned the campus as an “academical” village, a community of scholars, at least a mile away from the nearest town to lessen distractions from study.

The focus of both campuses was the library rather than a chapel or church, as was common at European universities. The libraries were both rotundas based on the Roman Pantheon, a temple dedicated to all the gods. Jefferson and Nichols, however, transformed the ancient structure into a modern “temple of learning.”

Mellown notes that this ideal of an “academical” village did not really match the realities of life in frontier Alabama, and rowdy students and discipline problems plagued the antebellum institution.

The installation of a military system of governance in 1860 improved discipline on campus, but it also had the unfortunate consequence of making the University a military target for Union forces during the closing days of the Civil War.

On April 4, 1865, Union troops almost destroyed the campus, leaving only the President’s Mansion, Gorgas House, Guard House, Observatory and a few assorted faculty houses around the periphery of campus.

“The records of the Board of Trustees, as well as other important University papers, were not destroyed,” says Mellown. “Fortunately, they were being kept in the President’s Mansion at the time and, thanks to the heroism of Mrs. Garland, the president’s wife, the mansion was not burned.”

Nichols’ plan was not used to rebuild the University. Since it was still a military school, the new campus was designed following the plans of Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Va.

Overseeing the construction of the new campus was Col. James Thomas Murfee, commandant of the University of Alabama Cadet Corps. The first building to be rebuilt was the Barracks (later named Woods Hall) constructed in 1868 in a Tudor Gothic style often employed in military schools.

The lower floor was used for classrooms while the upper floors were used for dormitories. The building is only one room deep and originally there were no internal connecting doors. After hours, cadets who tried to leave their rooms were observed by sentries posted in front of the building and given demerits.

Mellown says the University was enlarged when more money became available in the early 1880s, which led to the construction of Clark, Manly, and Garland halls. Designed by the New Orleans architect William A. Freret in the High Victorian Gothic style then fashionable, they provided more space for the growing University.

In 1903, the University abolished the military form of governance, and, in 1906, it was enlarged once again as part of the celebration of its 75th anniversary.

At this time the “Greater University Plan” envisioned a much larger campus designed on Beaux Arts principles featuring Classical Revival style buildings. Buildings from this era included Comer, Morgan and Smith halls.

In the 1920s, administrators added yet another layer to the campus when they adopted the “Million Dollar” master plan during Dr. George Denny’s administration. The plan added most of the buildings surrounding the main Quadrangle.

Buildings from earlier plans continued to co-exist with new structures, and planners managed to blend them into a harmonious whole. The architects for the Gorgas Library, for example, placed the large structure symbolically so that its massive front steps rest upon the foundations of the antebellum Rotunda.

During the 1960s and 1970s, examples of modern architecture were built on campus including now demolished Rose Towers, Tutwiler Hall and the Ferguson Center.

By the late l980s modernism had become outmoded, and postmodern had become the fashion. Postmodernism in architecture is not one style but many, and there are numerous variations of it at UA, Mellown says. In the new book, he identifies a number of variant styles including Neo-traditional and “Ironic Classicism” employed on the Moody Music Building and the Rodgers Library.

“There is a lot of new unpublished material about The University of Alabama and its architecture in the book,” Mellown says. “I think it will shed new light on the architectural significance of campus.”

Dr. Mellown is an associate professor emeritus in the department of art and art history within UA’s College of Arts and Sciences. His upcoming book will be published by The University of Alabama Press in Sept. 2013.