Twenty-seven years ago, Dr. William Keel, magnifying glass in hand, painstakingly pored over detailed photographs depicting as much of the southern hemisphere’s sky as wide-field photographic telescopes could capture.

Searching for particular types of astronomical objects within the 600 14-inch negatives, Keel invested roughly one hour a day – the maximum his eyes could endure – on the project. The task took 15 months.

“You can do that once a career,” says Keel, professor of astronomy at The University of Alabama.

Fast forward to the 1990s. The volume of images made available to astronomers worldwide is overwhelming. The Hubble Space Telescope, alone, can send 120 gigabytes of science data to researchers weekly. That’s the equivalent, the Space Telescope Science Institute points out, contained in about 3,600 feet of books on a shelf. Welcome, information overload.

COMPUTERS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR EYEBALLS

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which began operating in 2000, collects data robotically. It has captured images of millions of starts, nebulae and galaxies. To keep up, scientists turned to computer software to make preliminary analyses. However, as anyone who has ever hit ‘control,’ ‘alt’ and ‘delete’ knows, some things computers just can’t do as well as humans.

Take determining whether a particular galaxy should be classified as spiral or elliptical – a beginning point for many galaxy observations. Since computers can’t see the tell-tale whirlpool-like arms of a spiral galaxy or the football-shaped disc at the center of elliptical galaxies, software uses other means to make the classifications.

By focusing on things like a galaxy’s color or its “average brightness profile” and how those typically correlate to structure, computer software attempts to categorize galaxies, Keel says. Such computerized classifications are swift, but they aren’t as accurate as the human eye.

Astronomers, like scientists in many other fields, are turning in increasing numbers to “citizen scientists,” members of the general public who often have zero formal training in science but who have a keen interest in a particular topic and show both a willingness and an aptitude to contribute.

IT’S A ZOO

A project launched in 2007, known as Galaxy Zoo, is perhaps the mother of all citizen science astronomy projects. More than 300,000 people, from all walks of life, have logged onto galazyzoo.org and made more than 60 million classifications of objects from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Instructions and other site information can be displayed in five languages. Within weeks of its July 2007 inception, Keel became one of several professional astronomers intricately involved in the project.

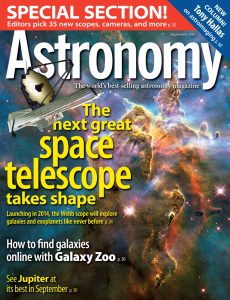

As the effort gained steam, various mainstream media outlets publicized it, sparking additional interest. Astronomy magazine invited Keel to author a full-length article about the project, publishing it in its September 2010 issue.

Anyone with an Internet connection can, following a brief online tutorial, participate in the latest project highlighted by Galaxy Zoo operators. Its scientific validity hinges, in part, on sheer numbers. Each image must be evaluated by at least 10 computer users, and unless at least 80 percent of them agree, the classification process starts anew.

The Internet, and the increasingly wired world, has opened group projects, including those involving citizen scientists, to an extent never before imagined.

“The wisdom of crowds – which frequently I don’t believe in, but, in this case – it’s panning out,” says Keel. “This could become an important piece in the way certain kinds of science is done.” Leading the effort are researchers at Oxford University and Portsmouth University in the UK and those at Johns Hopkins University.

BUT IT’S GENUINE

Galaxy Zoo’s key to success, says Keel, is ensuring the contributions of its participants, known as zooites, are real.

“The project must be one of genuine research importance,” Keel says.”Zooites’ contributions have to be more than legwork – no clicks wasted – and, intellectually, they are treated, as much as possible, as co-workers, as collaborators.”

The degree of initial interest in the project came close to becoming its undoing, Keel says. The professional scientists involved, known as the zookeepers, were inundated with questions from those logging in and wanting to help. Frustrations began to rise as astronomers were unable to keep up with the volume of e-mails. So, a discussion forum was added to the website, in hopes participants could help answer each other’s questions.

“Without meaning to, I ended up being the zookeeper who prowls the discussion forums,” Keel says. “It turned out to be an enormously valuable science asset because that became the safety valve for weird things to show up – for people who spotted odd things to discuss with each other.”

‘WHAT IS THE BLUE STUFF?’

A prime example of such oddness occurred when Hanny van Arkel, a primary school teacher from the Netherlands, came across the image of a strange gaseous object with a hole in the center while using Galaxy Zoo.

After seeing the oddly colored blob of gas and posting “What is the blue stuff?” on the site’s online forum, professional astronomers became interested in the unusual object. Later, astronomers, led by Keel, were awarded time on the Hubble Space Telescope to further analyze it.

The process created such a stir that the Space Telescope Science Institute awarded Keel and a collaborator a public outreach grant to tell the story of “Hanny’s Voorwerp,” Dutch for Hanny’s Object, via a comic book.

TRY THIS AT HOME

Try Galazy Zoo for yourself by visiting galaxyzoo.org, and join users from across the United States, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Brazil, Canada, Australia and elsewhere. But visit with caution, you might become hooked.

“People tell me it’s got some of the addictive quality of video games,” Keel says. “You’ve got to keep classifying because the next one might be one of the great big pretty spirals, and you’ve got to keep going until you get to it.”

Participants come from all walks of life. Keel regularly encounters zooites who range from a 16-year-old home schooler, to a retired emergency room physician living in London to a molecular analyst.

“One of the things I have been shocked at, over and over, is not just the breadth of interest, but the depth. There are people who got involved in Galaxy Zoo who became so interested in one problem they would teach themselves database query languages so they could go off and query the data archives and retrieve information and do their own collation,” Keel says.

“There’s been one spin-off project from Galaxy Zoo, initiated by zooites, who identified a particular class of very compact galaxies off odd colors and, basically, they made their case to astronomers that these were interesting and worthy of follow-up.”

While the direct benefits to the scientific community are important, Keel says there are other tangential benefits.

“One is that you now have a cadre of people from all walks of life and from all parts of the world who have immediate experience as to how science is done.” It’s also a multiplier, he says, in developing a more scientifically literate public.

“There are a fair number of zooites who go out and do Galaxy Zoo presentations in schools or astronomy clubs or in various venues.

NOT JUST ASTRONOMY

But, it’s not just astronomers who sometimes work alongside the general public.

Dr. Bernie Kuhajda, the collections manager in UA’s biological sciences departmentand a fish expert, routinely draws from the general public’s help whether he’s searching for a previously undiscovered species of trout in Mexico, rappelling inside caves in search of unusual cavefish or gauging the environmental health of a freshwater stream.

He remembers a trip to the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains in northwestern Mexico where not only the success of the project, but his very life, hinged, at least in part, on private citizens interested in helping.

“When you are doing work where there is no scientific record of where the fish occurs, it is extremely difficult to get around,” Kuhajda says. “There’s really no way to know who owns what.” On one Mexico trip, Kuhajda recalls a place less than ideal for an unassisted outsider.

“There are drugs being grown everywhere, and drug lords, and you definitely need local people to tell you where to go, when to go, and who to talk to so, you don’t get, one, lost, or two, shot.”

Others get even more directly involved in the science behind the projects, Kuhajda says. Shane Stacy, who works construction in Florence, and Randall Blackwood, who teaches science in a Huntsville high school, regularly help Kuhajda and his colleagues in research collection efforts within caves.

“They not only are the guides leading us into caves, getting permission from landowners and making sure geeky scientists don’t kill themselves in caves, but they have also collected some of the data for us. They have taken water temperatures for us. They have made counts of cave crayfish for us.”

CREATING A RESEARCH BASELINE

Martin Schulman, a former independent computer consultant whose degree is in philosophy, co-authored a scientific research paper with Kuhajda and others outlining some of the impacts an unexpected dam removal in Birmingham had on an endangered species, the watercress darter.

For a year and a half prior to the dam’s removal, Schulman and Elizabeth Salter, watershed organizer for the Alabama Rivers Alliance, had periodically taken water quality samples from Roebuck Spring through a citizen volunteer water monitoring program, Alabama Water Watch, and through the Watercress Darter Monitoring Program.

Following the dam’s removal, more than an estimated 11,000 watercress darters were killed. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, among others, became involved, and Kuhajda and collaborators began researching the impact.

“Without the data (from Schulman and Salter) before the dam was removed, we would not have had a baseline,” Kuhajda said.

DIGGING IN THE DIRT

More than 30 years ago, The University of Alabama’s Museum of Natural History established a baseline for partnering archaeologists and anthropologists with the general public in scientific digs. Through its annual summer expeditions, the museum has provided authentic scientific experiences through its field schools, available to those as young as 14.

Dr. John Hall, longtime assistant director of the UA museum and now director of the Black Belt Museum at The University of West Alabama, co-founded the event, which became a mainstay.

“We’ve discovered, among other things, probably the last acting Indian holy shrine at Moundville – from as late as 1500. We’ve done excavations at the old town of Saint Stephens in Washington County, the old state capital. We have found large dinosaur-aged reptiles, including portions of dinosaurs, and mosasaurs.

“We’ve dug in caves in north Alabama in which we’ve found giant ground sloths and bits of saber-toothed cats and bits of mastodon,” Hall says.

INCREASING SCIENCE LITERACY

He echoes Keel in saying the success of such projects is the seriousness of the ventures. The Museum’s program routinely attracts participants from across the Southeast and sometimes from other countries.

“You’ve got to make sure the program is genuine, that it is really science. And, you’ve got to ensure the parents that someone is watching out for their students.”

Both sides benefit, Hall says, and draw closer together. Professionals accomplish more than they could without the partnership, and the general public is enthralled by it. And, both groups, Hall says, also benefit in longer lasting ways.

“A scientifically literate public, particularly one who is experienced in science, can’t help but make better decisions in the future,” Hall says. “What we’re trying to do here is to give people an opportunity to participate so they can see the value of professional science. It’s not a panacea for all ills, but it doesn’t take a lot to demonstrate to people that science is a complex endeavor and that it works. We would like the public to see this.”

And while the Museum’s expedition has been in motion for more than 30 years, Keel says citizen science has been active for much longer than that, albeit not by that name.

“There has been citizen science going on for as long as there has been science,” Keel says. “There have been amateur astronomers staring through telescopes, faithfully comparing the brightness of stars and tracking the variations of pulsations for almost a century.”