At a two-day meeting of the British Cabinet in late 1862, the most powerful men in the United Kingdom were on the brink of intervening in the Civil War raging in America.

In a new book, Dr. Howard Jones, a university research professor at The University of Alabama, describes just how close Britain, and other European powers, came to stepping in between North and South.

“The nature of civil wars is that they attract outsiders – like vultures waiting to see what happens when this nation tears itself apart,” says Jones, author of “Blue and Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations,” published by The University of North Carolina Press.

“They’re waiting to do something. In the case of the American Civil War, it was horrific to begin with. Mathew Brady’s photos showed this; engravings in newspapers and magazines showed this. People could see the war before them by looking at photos, so they saw the grisly nature of the war.

“A humanitarian streak began to show itself in England. People began talking about the Christian obligation of civilized nations to stop the war.”

Jones’ book looks at the foreign entanglements surrounding the Civil War, particularly from the standpoint of Britain and France, two key players that saw opportunities in the conflict. Part of the problem European powers faced involved diagnosing what the conflict was about.

“Europeans looked at the war and said, ‘it’s all about slavery,’ ” says Jones, who researched the book over a period of 10 years, including trips to the United Kingdom to search through British Cabinet meeting minutes and other primary resources. “’That’s all they’ve been fighting about for the past decade or more.’

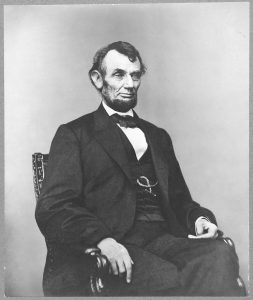

“(Abraham) Lincoln says, ‘no, it’s about preserving the Union.’

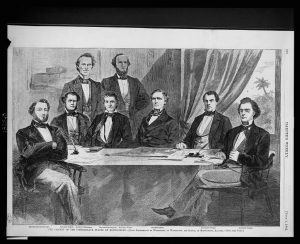

“(Jefferson) Davis insists that it’s about states’ rights. Lincoln thought the British would see through this argument and realize that if the Union won the war, slavery would eventually come to an end. But once slavery was considered not the cause, the British declared that the Union had become oppressive; ‘why can’t the North and South settle their conflict like we do in Europe – simply divide the country?’”

So, the South had some sympathetic ears in Europe. France, for example, under the leadership of Napoleon III, saw the opportunity to use its foothold in Mexico to retake the land lost in the French and Indian War in the 1700s.

“Napoleon III was a loose cannon,” Jones says. “France’s objective over all these years was to get back onto the North American continent. Napoleon I tried it, and it didn’t work out. Napoleon III tried again. He had this cockamamie scheme to install Archduke Maximilian from Austria as king of Mexico and build a monarchy that would be a magnet to bring in trade.

“His vision was, ‘We will grant the Confederacy recognition if the Confederacy would then support us in Mexico.’ In Napoleon’s “Grand Design for the Americas,” the Confederacy would serve as a buffer state between the Union trying to expand South and any other problem that might arise. France intended to establish an empire that extended from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific and greatly affected the European balance of power.”

Napoleon III’s plans did not work out, of course, and eventually Maximilian’s reign in Mexico fell with his death by a firing squad. Britain, however, remained the power likeliest to intervene. Britain craved the cotton the South produced, but the Civil War happened to start when a glut of the commodity was sitting on the market.

“Unfortunately for the South, fortunately for the Union, the South had had two bumper crops before the war,” Jones says. “The British and the French had just bought up enormous supplies of cotton and had a surplus. So they could depend on that surplus for over a year. The South wanted to play King Cotton diplomacy, but it had no leverage.”

Another factor – the Emancipation Proclamation issued in 1863 that freed slaves in the Southern states occupied by the North – is often seen as a move to keep Britain out of the war. But Jones points out that the proclamation had nearly the opposite effect.

“So many people argue that the Emancipation Proclamation stopped the British cold,” Jones says. “But, if you look at the play of events day by day, when Lincoln announced the proclamation, it was denounced in both England and France as one of the cheapest, hypocritical stunts you could imagine.

“‘Lincoln is losing the war, so now what is he trying to do? Destroy the South from within by stirring up slave revolts that could grow into an all-out racial conflict. We need to step in,’ some people said, ‘and stop this war before it gets totally out of hand.’”

And that’s just what the British government came close to doing at that two-day Cabinet meeting in 1862. The key players were Lord Palmerston, the prime minister, and Lord Russell, the foreign secretary. Both men were poised to intervene with the idea that the Civil War, with its heavy casualties, threatened to send the entire North American continent and the world into political and economic chaos.

But the meeting took place soon after the Battle of Antietam – a loss for the South and a battle with horrific casualties – and that battle was enough to turn the British against an intervention that could involve them in the war. Getting between the North and the South proved too costly and frightening to contemplate.

“Ultimately, the vote was overwhelmingly “no,” because the secretary for war, Sir George Cornwall Lewis, warned the British Cabinet that ‘if we enter this war, we will be at war on the side of the slaveholding Confederacy and against the Union,’” Jones says. “And there was no telling when it would end. The Cabinet members decided not to get involved and let the war play itself out.”