Energy Experts Find Key Links Between European Site, Domestic Oil Fields

by Chris Bryant

How are Portugal, Escambia County, Ala., and researchers in The University of Alabama’s Center for Sedimentary Basin Studies related? Well, each plays a role in this nation’s efforts to improve the recovery of domestic oil. And this is quickly becoming a near vital effort.

The law of supply and demand — as it relates to energy resources — may soon smack this nation in the face.

America is about to confront its most serious energy shortage since the oil embargoes of the 1970s, according to the National Energy Plan released by the Bush administration earlier this year. During the next 20 years, oil consumption is expected to rise 33 percent and natural gas by more than 50 percent, according to Energy Information Administration estimates.

In addition to conserving energy, improving products’ energy efficiency, and repairing and expanding gas and oil pipelines, refineries, electric generators and transmission lines — ask California about the importance of those last two — the report calls for increasing energy supplies while protecting the environment.

Dr. Ernest Mancini, professor of geology, directs the UA Center for Sedimentary Basin Studies that integrates the work of geologists, geophysicists, petroleum engineers, paleobiologists and computer scientists — all of whom work together to find environmentally feasible ways of increasing oil supplies.

In one of the Center’s projects, a $1.3 million effort sponsored, primarily, by the U.S. Department of Energy, researchers began exploring ways to improve the recovery of oil from the Appleton and Vocation oil fields in the Alabama counties of Escambia and Monroe, respectively. When the project began in September 2000, representatives of the small independent oil firms Longleaf Energy Group, Strago Petroleum Co. and Paramount Petroleum Co., became active participants and beneficiaries of the research.

However, since the UA researchers’ effort began, some larger companies have taken note of their work. “In December, we had requests from six companies, including BP, Total, and Shell, asking for more information,” Mancini said.

To understand the industry giants’ flurry of interest in the UA work, one has to go back a bit in time — about 155 million or so years ago, the researchers say — to the Upper Jurassic period. At that time, the site of today’s Appleton and Vocation oil fields lay underneath the ocean, as did all the southern part of the state, Mancini said.

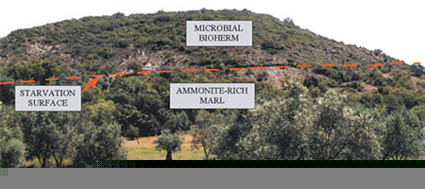

“During this time in the Earth’s history, conditions were optimal for the formation of microbialites in certain areas,” Mancini said. Microbialites are rock-like structures produced over hundreds of thousands of years by microorganisms depositing sediment.

Oil reservoirs typically involve multiple layers of rock, and oil is present in the pores of the rocks. Since each rock type has its own characteristics, it’s vital to the extraction process to understand which rock types are present and how they are distributed throughout the area. The clearer the understanding of the architecture of these underground rock formations, the better-equipped researchers are to suggest exploration and recovery strategies.

A variety of techniques are used to try to understand what the underground rock make-up is like, Mancini said. One such method is obtaining samples by drilling and then preparing and analyzing thin samples. This can be a time consuming and expensive procedure and does not provide an accurate representation of the larger scale changes that occur in the rock strata.

Dr. Joe Benson, a professor of geology and an associate dean in the College of Arts and Sciences, said the samples tell researchers about the rock types in the area and, subsequently, the porosity and permeability of those rocks. Such information is key in determining how oil flows within the rocks and identifying barriers to that flow. The amount of information provided by such samples is, however, limited.

“You might have a 3-inch core of rock from one location and another core one mile away,” Benson said of the samples. This doesn’t tell researchers anything about the areas lying between the samples. Another tool used by researchers is three dimensional seismic imaging. Sound waves projected into the reservoir area reflect back to the surface. Researchers see the reflections, indicators of where the rock types change. “What that doesn’t do so well is tell you the nature of the rock,” Benson said.

During the course of their work, researchers in the Center for Sedimentary Basin Studies pored over academic journals written by scholars from across the globe. They discovered writings detailing two locations in Europe, one in France and the other in Portugal, where similar types of microbial reefs were present, but were located above the ground, in what the researchers call “outcrops” or surface exposures. A lack of time and resources prevents most oil industry geoscientists from reviewing large volumes of scholarly literature. “Only an academician would stumble upon this,” Mancini said.

A series of letters and e-mail exchanges with European researchers ensued, and soon the UA researchers were arranging trips to see these European outcrops firsthand.

Unlike isolated underground core samples, the large stretches of the microbial reefs rising above the ground some 100 feet enabled the UA researchers to follow the rock type laterally for hundreds of feed. The UA researchers were even able to easily remove samples of the above ground reef and bring them back to the laboratory for further analysis.

The reefs in Portugal were strikingly similar to those in Escambia County. Enough so, that the UA researchers were able to use them as analogs in the development of computer models that predict more efficient ways to recover the oil from under the ground.

Through technology transfer workshops, held about a dozen times each year, Center representatives share their findings with the industry. Although the Center’s work related to the Appleton and Vocation oil fields was designed, primarily, to assist the small, independent operators drilling for oil in these specific areas, the Center’s ability to develop better computer models of Appleton — thanks to locating the geologically similar reefs in Portugal — turned many heads.

“These same types of microbial reefs are now being recognized in geologically younger and older rocks than those found in Escambia County,” Mancini said. They are also present in the North Atlantic and in the Outer Continental Shelf of the Gulf of Mexico. “It looks like the little Appleton model has global applicability,” Mancini said.

Dr. William Parcell, who came to UA as a doctoral student four years ago, said the research trips to Europe were the highlight of his time as a University of Alabama student. “It wasn’t just a faculty trip,” Parcell said, “the students got to go, too. The opportunities I got here were beyond what I expected. It was everything I wanted it to be — and more,” the recent graduate said.

Parcell said a professor from the University of Birmingham, England, who had worked with the microbial reefs, met the group in France. That professor then invited Parcell to return with him to England to meet other researchers and to view their work. He jumped at the chance. “It’s one thing to read about it in the literature, but it’s another to go see it,” Parcell said.

During his time as a UA graduate student, Parcell estimated he authored or co-authored more than 40 scholarly papers and presentations. “Here, I felt like I was really involved in the work and was an active part of everything,” Parcell said. “I was able to make a lot of contacts and to publish, and that’s what you need to do to get a job.”

It worked for Parcell as he started his career as an assistant professor at Wichita State University in August. He said the opportunity to work with researchers, such as Mancini, was invaluable.

“He’s an enthusiastic adviser,” Parcell said of Mancini, “and being enthusiastic about the work he does shows through in the projects he helps direct and in the classroom.”

Another project where UA researchers involve their students is in their efforts to improve the ultimate recovery of and extend the productive life of the Womack Hill oil field in Alabama’s Choctaw and Clarke counties. Researchers are in the midst of their second year in that six-year, $8 million project, also primarily sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy.

It too has international implications as the type of limestone rock found at Womack Hill occurs across the Gulf region and is present in other areas of the nation and the world. The information gathered and knowledge gained about these rocks are shared with Pruet Production Co., the small independent oil company that operates Womack, and will be passed on to other companies.

Extending the life of fields, such as Womack Hill, can generate a solid return on an investment, Benson said. “It’s very expensive to go out and explore for a field,” he said. Exploration and infrastructure costs can be staggering — costs that are nonexistent when working to improve ultimate recovery rates from existing fields. Improving recovery techniques can prevent premature abandonment of a field, Benson said. “In those cases, you are producing oil that, otherwise, would not have been produced, because of a better understanding of where it is and how best to recover it.”

Benson said the hands-on opportunities UA gives to its students interested in oil and gas research are uncommon. “There are, perhaps, a half dozen schools in the country that offer this type of opportunity,” he said.

And if the pending energy crisis is as significant as predicted, UA’s expanding research opportunities in these areas are arriving at a very opportune time.

Contact

Drew Wood or Linda Hill, UA Media Relations, 205/348-8325, lhill@ur.ua.edu

Source

Dr. Thomas Fox, professor and chair, modern languages and classics, 205/348-5054, tfox@bama.ua.edu